Strategic Portfolio Construction and Asset Allocation for Sustainable Long-Term Investment Performance

Why Portfolio Construction Matters More Than Asset Selection

In the discourse of long-term investing, attention is often disproportionately directed toward asset selection—identifying winning stocks, high-yield bonds, or alternative investments with superior expected returns. However, decades of empirical research and real-world investment outcomes consistently demonstrate that portfolio construction and asset allocation are the dominant drivers of long-term performance and risk control.

Rather than asking “Which assets will perform best?”, institutional investors and sophisticated individuals increasingly ask a more fundamental question:

“How should capital be allocated across assets to achieve resilient, risk-adjusted returns over time?”

This article provides an in-depth examination of portfolio construction and asset allocation strategies designed to support long-term investment performance. It integrates financial theory, empirical evidence, and practical implementation considerations, while acknowledging the limitations and trade-offs inherent in real-world investing.

1. Conceptual Foundations of Portfolio Construction

Portfolio construction is the structured process of combining assets into a cohesive investment portfolio that aligns with specific objectives, constraints, and risk tolerances.

Core Objectives of Portfolio Construction

At its foundation, portfolio construction seeks to balance three often competing goals:

- Return optimization: Achieving sufficient expected returns to meet long-term financial objectives.

- Risk management: Controlling volatility, drawdowns, and tail risks.

- Consistency: Delivering stable performance across different market regimes.

These objectives are constrained by factors such as investment horizon, liquidity needs, regulatory requirements, tax considerations, and behavioral limitations of investors.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT): A Starting Point, Not a Destination

Introduced by Harry Markowitz in 1952, Modern Portfolio Theory formalized the idea that:

- Risk should be assessed at the portfolio level, not at the level of individual securities.

- Diversification can reduce unsystematic risk without necessarily sacrificing expected return.

- Efficient portfolios lie on the efficient frontier, offering the highest expected return for a given level of risk.

While MPT remains foundational, its assumptions—normally distributed returns, stable correlations, rational investors—are often violated in practice. As a result, modern portfolio construction extends beyond MPT rather than relying on it exclusively.

2. Asset Allocation as the Primary Driver of Long-Term Returns

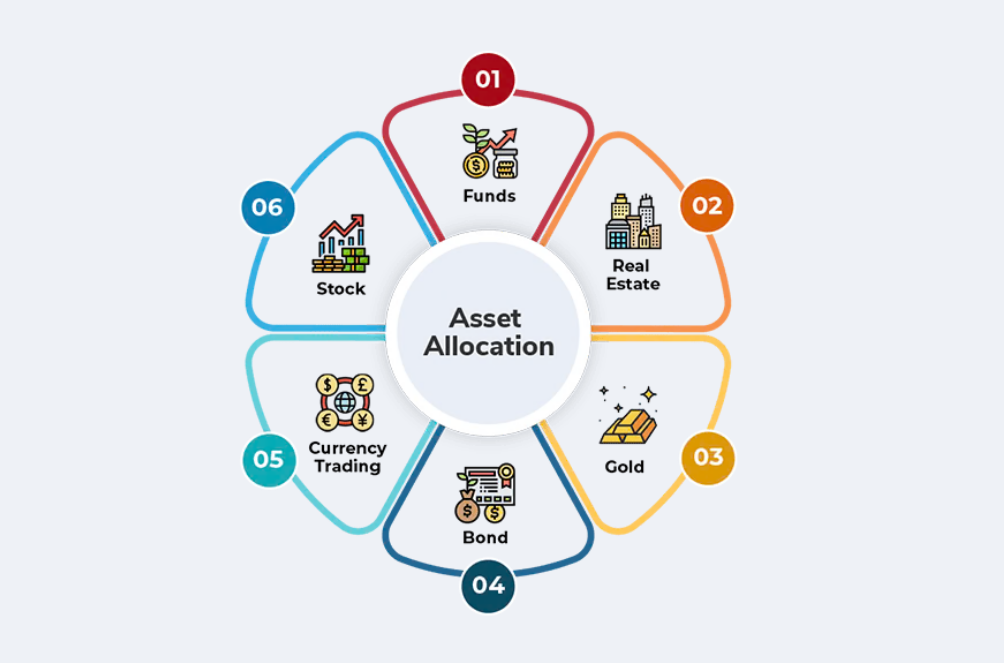

Asset allocation refers to the strategic distribution of capital across broad asset classes such as equities, fixed income, real assets, and alternatives.

Strategic vs. Tactical Asset Allocation

A clear distinction must be made between two allocation approaches:

- Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA)

- Long-term, policy-driven allocation

- Anchored to investor objectives and risk tolerance

- Changes infrequently

- Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA)

- Short- to medium-term deviations from strategic weights

- Based on valuation, macroeconomic signals, or momentum

- Requires strong governance and discipline

Empirical studies suggest that strategic asset allocation explains the majority of portfolio return variability over time, while tactical adjustments play a secondary, more uncertain role.

Core Asset Classes and Their Economic Roles

A well-constructed portfolio recognizes that asset classes serve different economic functions:

- Equities

- Primary engine of long-term growth

- High return potential, high volatility

- Fixed Income

- Income generation and capital preservation

- Diversification during equity drawdowns

- Real Assets (e.g., real estate, infrastructure)

- Inflation hedging

- Stable cash flows

- Alternative Investments

- Low correlation potential

- Complexity and liquidity trade-offs

The challenge lies not in identifying these assets, but in determining appropriate weights and interactions among them.

3. Risk-Based Approaches to Asset Allocation

Traditional portfolios often allocate capital based on nominal asset weights (e.g., 60% equities, 40% bonds). However, this approach ignores how risk is actually distributed.

Risk Contribution vs. Capital Allocation

In many traditional portfolios:

- Equities contribute 80–90% of total portfolio risk

- Bonds contribute relatively little risk, despite large capital allocations

This insight has given rise to risk-based allocation frameworks, including:

- Risk Parity

- Assets are allocated such that each contributes equally to total portfolio risk

- Often results in higher bond exposure, sometimes with leverage

- Minimum Variance Portfolios

- Focus on minimizing overall portfolio volatility

- Can suffer from concentration and regime sensitivity

While risk-based approaches offer diversification benefits, they are not inherently superior and may underperform during inflationary or rising-rate environments.

4. Diversification Beyond Asset Classes

True diversification requires moving beyond simplistic asset-class labels.

Dimensions of Effective Diversification

A resilient portfolio diversifies across multiple dimensions:

- Geographic: Developed vs. emerging markets

- Economic exposure: Growth-sensitive vs. defensive assets

- Factor exposure:

- Value

- Size

- Momentum

- Quality

- Low volatility

- Time horizon: Staggered investment and rebalancing schedules

Crucially, diversification should be evaluated during periods of stress, when correlations tend to converge and diversification benefits are most needed.

5. Asset Allocation Across Market Regimes

Markets are not static. Inflation, growth, interest rates, and policy environments evolve over time.

Regime-Sensitive Allocation Frameworks

Long-term portfolios increasingly incorporate regime-aware principles:

- Growth-driven environments

- Favor equities, credit, cyclical assets

- Inflationary environments

- Emphasize real assets, inflation-linked bonds

- Recessionary environments

- Increase high-quality fixed income, defensive equities

- Crisis environments

- Liquidity and capital preservation take precedence

Rather than frequent trading, regime awareness informs structural tilts and stress testing.

6. The Role of Rebalancing in Long-Term Performance

Rebalancing is often underestimated despite its critical role in portfolio discipline.

Why Rebalancing Matters

Over time, asset performance causes portfolios to drift away from target allocations, leading to:

- Increased unintended risk

- Behavioral biases (performance chasing)

Rebalancing enforces a systematic “buy low, sell high” mechanism.

Rebalancing Approaches

Common approaches include:

- Calendar-based rebalancing

- Fixed intervals (e.g., annually)

- Threshold-based rebalancing

- Triggered when allocations deviate beyond set bands

- Hybrid approaches

- Combining time and threshold rules

The optimal approach depends on transaction costs, taxes, and governance capacity.

7. Behavioral Considerations in Portfolio Construction

Even the most theoretically sound portfolio fails if investors cannot adhere to it.

Common Behavioral Pitfalls

Long-term investors frequently encounter:

- Loss aversion during drawdowns

- Overconfidence in favorable markets

- Panic selling in crises

Effective portfolio construction therefore integrates behavioral constraints, such as:

- Smoother volatility profiles

- Clear investment narratives

- Explicit downside risk management

In this sense, portfolio construction is as much a psychological engineering problem as a financial one.

8. Practical Constraints and Implementation Challenges

The translation from theory to practice introduces significant complexity.

Key Constraints

- Liquidity needs

- Tax efficiency

- Regulatory limits

- Transaction costs

- Operational feasibility

Ignoring these constraints can lead to portfolios that are theoretically optimal but practically unviable.

Institutional vs. Individual Contexts

Institutional investors benefit from:

- Long horizons

- Governance structures

- Access to alternatives

Individual investors, by contrast, require:

- Simplicity

- Transparency

- Cost efficiency

Portfolio construction must be tailored accordingly.

9. Evaluating Long-Term Portfolio Performance

Performance evaluation should extend beyond headline returns.

Key Metrics for Long-Term Assessment

- Risk-adjusted returns (e.g., Sharpe ratio)

- Drawdown magnitude and duration

- Consistency across market cycles

- Alignment with stated objectives

Importantly, benchmark selection should reflect portfolio structure and risk profile, not arbitrary market indices.

Conclusion: Portfolio Construction as a Strategic Discipline

Long-term investment success is not the product of superior forecasting or asset selection alone. It is the outcome of disciplined portfolio construction, grounded in sound asset allocation principles, robust risk management, and realistic behavioral assumptions.

Key takeaways include:

- Asset allocation is the dominant determinant of long-term outcomes.

- Diversification must be multidimensional and stress-tested.

- Risk, not capital, should be the central unit of analysis.

- Behavioral and practical constraints are integral—not secondary—considerations.

Ultimately, effective portfolio construction transforms uncertainty from an enemy into a manageable feature of long-term investing. In doing so, it provides investors with not only competitive returns, but also the resilience required to stay invested across decades.

References (Selected)

- CFA Institute – Portfolio Management and Wealth Planning Curriculum

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio Selection, Journal of Finance

- Ilmanen, A. (2011). Expected Returns, Wiley

- Investopedia – Asset Allocation & Portfolio Construction